Exploring Celtic Origins – The Gale and ALBA – BC to early AD – Part 1

My first blog ‘The Misty Origins’ was a look at how far back our Celtic blood line goes and where those Celts came from, I also touched on the ancient name of Scotland (Alba) and some of the stories of the ancients regarding the British Isles from the classical writers and their chronicles; namely the Greeks, Romans, and Iberians. While writing ‘Misty Origins’ it was obvious that there was so much more Tales and Legends to explore regarding our Celtic past, their language and culture, and their legacy; I said that I would come back and look into some of the stories in more depth by explaining my take on some of those Legends and Stories. Therefore, after adding a number of new books and some old publications to my collection I have spent more than a year reading and researching before finally put together the following analysis on my part to bring to the reader a story that is informative, interesting, plausible, and hopefully enjoyable. I have given this transcript the heading above and will over the next year or more set out a number of stories in chronological order regarding Scotland’s ancient history, legends and myths. As the title above suggest this is a look to a time in history when the nation of Scotland was not in existence as we know it, although the mountains, glens and rivers are the same, everything else is different. To understand where we came from, the people, the culture, and the nation that Scotland is and has been for a longer time than most, we have to go back to the early beginning’s to try and understand how far back in time the root and branch of the Scot’s has existed.

According to the Scottish historical novelist Nigel Tranter, “The beginnings of history are shrouded in myths and legends, both have a root back to the origin of a story or event, from the oral tradition of storytelling. This is the stuff of caricature but like all stereotypes it embodies elements of the truth”. Therefor with this in mind I have taken my research and written the following story with as much history and archaeological evidence as possible along with an open mind.

In recent years, from around the early nineteen seventies to the present time, the exploring of Celtic origins has brought new ways forward in archaeology, history, linguistics, and genetics with all four working closely with each other to bring new evidence, idea and theories on the origins of the Celts. For over 300 years there has been traditional interpretations by many scholars and despite some disagreement their beliefs have not altered too much and have been the main stay for Celtic history, language and culture.

However, in my Quest to collect more publications and papers on Scottish and Celtic history I have recently come into contact with a very exciting and revolutionary new book (Exploring Celtic Origins – New ways forward in archaeology, linguistics, and genetics) the book has new radical and very different ideas of Celtic Origins. Published in 2019, Edited by Barry Cunliffe and John T. Koch of the Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies in Aberystwyth, the book focuses on a research programme in collaboration with the School of Archaeology, university of Oxford, designed to explore the origin of the Celts and of the Celtic language family. It provides a wealth of data and interest for the researcher. The revelations are revolutionary, radical and totally different from the age long traditions of the last 300 years.

The Celts from the west idea was formulated by Barry Cunliffe on archaeological evidence and was first published in his book -Facing the Ocean (2001). Then a number of publications between (2013 – 2019), from the Advanced Celtic Studies Centre, exploring ‘The Celtic from the West’ meets linguistics and genetics investigations. Old cherished beliefs have to be modified or abandoned regarding the Celts as fascinating new visions and theories come to light.

The following is a very brief attempt on my part to summarise the research and data that has been produced and published for – Exploring Celtic Origins – and the Celts from the West idea.

The new hypotheses that the Celtic people first emerged along the West Atlantic maritime sea zone means that the traditional interpretations, which have been around for over 300 years, simply do not work anymore and have to be discarded as new hypotheses take their place.

In 1707 the Oxford antiquarian Edward Lhugd published the Archaeological Britannica and his linguistic findings identified two broad linguistic groups of Celtic language, Gaelic of the Irish and Scots and Brittonic of the Welsh and Cornish but offered no explanation of why there had emerged a difference between the two groups. Later scholars referred to these different groups as Q-Celtic and P-Celtic, this derives from the fact that Q- Celtic tongue preserves the Indo-European qu whereas the P-Celtic transformed the qu into p.

The traditional view was that the Celts and their language originated in central Europe from Hallstatt in Austria and La Tène in Switzerland where excavations produced a massive collection of Celtic artefacts in both countries between 1846 and 1857. Here was tangible evidence of the Celts who, according to the classical texts, began to settle the Po valley and the Alps around 500 BC. The Celts now had an archaeological identity and the advance of the Celts during the migration period was traced by the distribution of La Tène material culture. This in turn led to the assumption that the appearance of artefacts made in the La Tène style was proof of mass movements of Celts from central Europe spreading into the West of Europe and later into Britian and Ireland and was a representation of an invasion of Celts, indeed there may have been multiple Celtic invasions to the west. So, this was the traditional hypothesis that the Celts moved from central Europe westwards and eventually colonizing Britain and Ireland, this was unchallenged for nearly three centuries, with only slight modifications. Another invasion to the southwest was proposed to explain how the Celtiberians of Spain came to be spoken.

By the second half of the 20th century some archaeologists began to express doubts with the traditional model that there had been an invasion of Celts from a middle European Celtic homeland. There was no convincing evidence of invasion either in the Hallstatt or La Tène Iron Age period nor was there anything to suggest a significant inflow of population in the preceding Late Bronze Age into Britain, Ireland, and Iberia. Instead the evidence from Quality and much more advanced archaeological data was showing that an indigenous development of people through existing social networks were linked along the Atlantic sea coastal zones. The Atlantic maritime zone became one of the corridors along which human populations moved to colonize new territories that had many attractions for the hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic. The introduction of farming to the Atlantic zone during the Neolithic period was complex but the evidence shows that it spread from Asia Minor in part by new people and was rapid taking as little as 1500 years to reach the Atlantic shores. These coastal farming communities began to develop networks of communication that can be traced through the development of passage graves, stone-built grave chambers, the earliest passage graves are found in Portugal about 4800 BC – by the end of the 4th millennium they were being built as far north as the Orkney Islands.

Next came the Beaker phenomenon about 2800 BC saw the rapid expansion of connectivity through western Europe, not only through the Atlantic sea routes but inland via the river systems both in mainland Europe and Britian. This was a period of enhanced mobility of both materials and people with the desire for metals as a prime cause of this new mobility. What is of particular significance here is that the transmission of these complex ideas and values over so large an area implies the development of a common language over the 2 to 3 millennia under decision here. The hypothesis, then, was that the Atlantic language may have absorbed influences from other Indo-European language families encountered along the Atlantic façade and perhaps also from languages spoken by the indigenous hunter-gatherers that developed in the 5th and 4th millennia was Proto-Celtic and that the vector for its extension into middle Europe was the Beaker phenomenon. It was during the Beaker period that the mature Celtic language developed and reaching a peak during the Atlantic Late Bronze Age (c.1300-800 BC). People communicated freely using a common language and shared a broadly similar value system and material culture that differed very little from region to region. It was during this age that the Celtic language continued to develop, its regional dialects converging to form a single language comprehensible throughout. A chieftain from the Shetland Isles would not have felt out of place in the Algarve and might have been able to join in with the conversation at a feast.

A significant change in the 9th century BC came when Phoenician traders from the east Mediterranean began to set up trading posts and colonies along the Iberian coastline disrupting the old Atlantic Late Bronze Age system. This brought about the first dislocation and could explain the divergence between Hispano-Celtic and the rest of the Atlantic Celtic speakers. About 600 BC a second dislocation can be identified in the archaeological record and there is ample evidence that Iron Age France, the British Isles, and Ireland were part of complex exchange network in the distribution of similar artefacts across much of the region. After 600 BC Ireland and Scotland seem to fall out of the exchange network and enter into a period of isolation. This could explain the divergence of the Goidelic language family, which evolved in Ireland and Scotland eventually to become Scots Gaelic and Old Irish, from the Gallo-Brythonic of the rest of Britian and Gaul. While the Brythonic branch survived to become Welsh and Cornish and contributed to Breton, the Gaulish language largely died out under the impact of Romanization.

The above summary is only a brief glimpse of the new hypothesis Celts from the west theory and I would recommend reading the books to understand the full complexity of the program of research that has taken place and indeed is still continuing.

I had begun to re-think some of the traditional history and archaeology of Scotland before reading the (Celts From the West) and (Exploring Celtic Origins) the books have given me a whole new emphasis and enthusiasm in my own search for more knowledge and specific information on Scotland’s distant past.

The unfortunate fact is Scottish history was tampered with and destroyed by Edward the First of England then Oliver Cromwell committed some horrendous crimes and finally the religious zealots of the reformation caused untold damage to any remaining records. What ancient documents remain is sparse and very patchy with only legends, myths, and stories to relay on. There is some recorded information from other countries such as Ireland where their recorded history has largely been maintained, where the researcher can find snippets of information on Scotland in the Irish Annals. However, sometimes there is a hint of fiction or proper gander when reading such documents. What is myth, legend or the truth.

There is an interesting literary source for Ancient Celtic Ireland (The Book of Invasions). In a passage it refers to Japhet son of Noah and how the people of Europe derive from him and his sons and their sons, the passage rambles on a bit, until it comes to the third son of Elanius, had four sons: Romanus, Francus, Britus, Albanus. It is Albanus who took Alba [(North) Britian] first, and it is named Alba after him; then he was driven across Muir nIcht by his brother Britus, so that Albania on the Continent is derived from him (‘today’). The fact is it refers to the North (Scotland) as Alba. Is it just myth or legend? Or is there an element of fact within the myth? There are a number of other similar versions of the Japhet son of Noah myth and of course it has biblical justifications with the story of Noah and the Great Flood. Japhet is also mentioned in one of the Pictish Kings Lists – King Cruithne was Mac (son) of Cinge, Mac Luthtai, Mac Parthalan, Mac Agnoinn and so on right back to Japhet or Japhelth Mac Noah. More myth or legend?

There is an interesting passage from an old book (History of the Scottish Nation Volume 1, James A. Wylie – 1886) that tells the story of the sons of Japhet and their migration into Europe. I have condensed the story the best I could here.

From their starting point in the highlands of Armenia, on the plain of Euphrates, two great pathways offer themselves by either of which their migrating hardy hordes might reach the shores of a distant land.

The Great Japhethiean family split with one branch goes to the North and descends the great slope of northern Asia branching out and winding their way through a boundless maze of rivers, meadow and Boags, forest and mountains until the head of the hordes reached the northern shores of the flatlands of Europe, from where they could cross the narrow stretch of sea to the far off-land on a fleet of crafted canoes made out of the trunks of felled oak.

The other branch of the Japhethiean family moved south into Lebanon from where they became the horde of slaves that left Egypt of old and after ‘forty years, in the great terrible wilderness emerged along the shore of the western Mediterranean and crossed over into Spain by the Straits of Gibraltar where they settled in the north for a time before migrating once more to the great island’s to the north and up the west coast of the main island. Though sprung of the same stock, they came in this way to unite the qualities of different races and climes – the gravity of the Occident with the warm and thrilling enthusiasm of the Orient. Here is a suggestion that the early peoples of the British Isles were from the same root or family but had split and branched off in their different directions before arriving with one branch to the north and east and the other to the south and west. Although from the same root both branches of the same family had diverse with the addition of other cultures that they had encountered on their long journey. Of course, this is the same Noah and Japhet story from the Old Testament of the Bible.

Other scholars were mentioned in the above book such as Pinkerton; ‘in his learned “enquiry into the History of Scotland” he claimed that the north and east of Britain were peopled from Germany however, it is not clear from what period of history he is referring to, and although there may have been some small migration of people from Germany in more recent history to Scotland, the Germanic people were not in that part of Europe as far back in the period mentioned above, which is many millennia BC. One can see how difficult it is to the researcher when trying to decipher old text and history books.

There is the obvious links to the Book of the Old Testament Exodus and other scriptures of the same First Book of the Bible with much of what is written in many older history books from all over Europe, all very much written with a similar theme but, often with a lot of diversification to suite the history of a particular country or nation. In Scotland’s past literary history there have been a number of connections to Egypt and Scota the daughter of an Egyptian Pharaoh and from her comes the name of the Scots (there is more about Scota further on). Also, there is a strong link to northern Spain and Portugal to Scotland both in literary history and archaeology. I remind the reader of what Nigel Tranter said to me many years ago when I was lucky to meet him: “The beginnings of history are shrouded in myths and legends; both have a root back to the origin of a story or event”. Therefore, we must keep an open mind and always search for the facts as much as possible.

The early Irish Annals refer to Scotland as Alba or Alban and sometimes as “Albion”, therefore this name was well knowing by various peoples of early Europe, as the name of what is now Scotland. The early Basque and Celtic Iberian seafarers also navigated around the British Isles and were familiar with the North as Alba or Albion where they were involved in trade as well as settlements around many parts of the Isles, over many years as far back as 4000BC. The name Alba is therefore the name given to the land of the high, white caped, mountains of the far north of those mysterious Isles.

As yearly as 300BC a Greek seafarer Pytheas refers to the British islands as Pretanikai Nesoi (meaning “Pretanic Islands”); the Reverend A.B. Scot, in his 1918 book (The Pictish Nation, its People and its Church) claims the name is based on the native name for Britian (Ynis Prydain), which literally means Picts’ Island. The scholar, Kenneth Jackson derives the name “Pritanic” from the Pictish tribe called Pritani, meaning “The People of the Designs. There is an interesting attribute to the name (Pict) the P-Celtic speaking people spelled (Pict) Pryten, this eventually becomes Briton in the tong of the Teutonic invaders, and is now Britian as in British; which never was and never will be a nation!

The later Irish Annals of Ulster refers to Alba as Cruithintuait, the word Cruithni (meaning “The tribe of the Designs)- this being the Irish name for the Picts, and tuath for the people, land or nation. This may come from an early Irish legend that claims a new group of Iberian settlers arrived in Iern (Ireland), the Irish called these new people “Cruitnii”- or the people of the Designs”, these people were the Picts according to Irish legend. The legend goes on to say that, Heremon – one of the first Milesian King of Ireland who along with his eldest brother, Heber, reigned together in conquering Ireland around (c. 1698 B.C.). Heber was slain in battle and Heremon reigned as sole King thereafter. During Heremon’s reign the Picts arrived in Ireland and requested Heremon to assign them a part of the newly – conquered country to settle in, but he refused. The legend also claims the Picts (“Cruitnii”) had not brought wives with them, Hereman gave them wives the widows of the Tuatha de Danaans, whose husbands had been slain in battle by the Iberian Celtic invaders, he then sent them with a large party of his own forces to conquer the country to the east called “Alba”. The conditions that were placed on the Picts were that they and their posterity should be liege to the Kings of Ireland and that all bloodlines should pass through the wives. This is obviously Irish or Irish Scots propaganda at play, and I will return to this matter a little further on. Notice that the country to the east was named as Alba and the date was around c.1698 BC.

The ancient Basque people of Northern Spain were once known to Rome as the Pictones. Could the Picts be Descendants of the ancient Basque? There is a possibility because the early Basque seafarers navigated around the British Isles and may have established colonies or trading posts around the east coast of Alba (Scotland) in particular. However, I am not aware of any Basque names in Scotland that might have survived to this day? If there were colonies perhaps, they were assimilated by other Celtic tribes over time? The other problem is the Basque language is not Celtic and is more directly related to an early Indo-European langue.

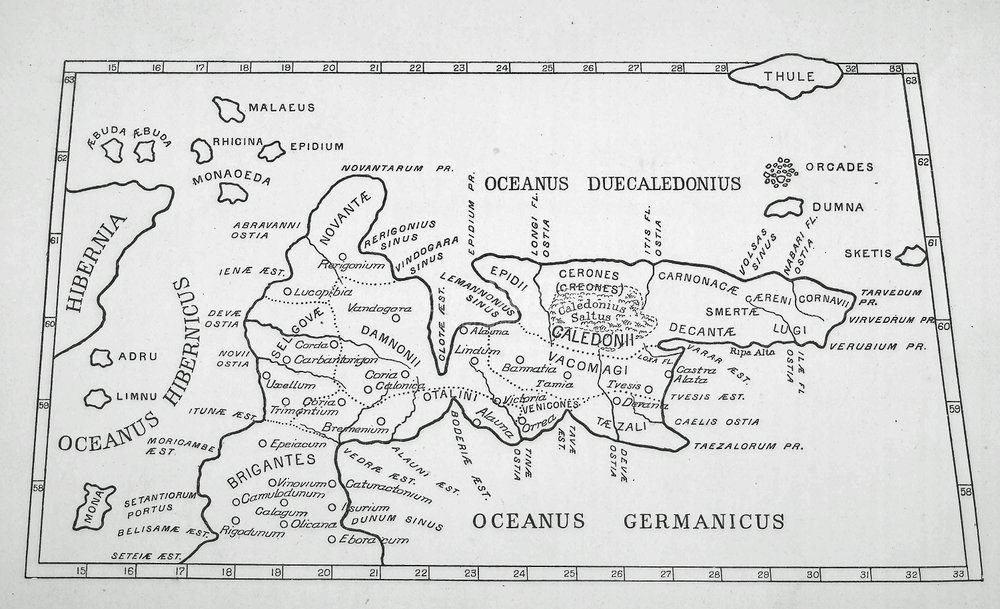

One of the earliest recorded mentions of the Celts – as (Keltoi) was by Hecataeus of Miletus, the Greek geographer, in 517BC, when writing about people living near Massilia (modern Marseille). In the fifth century BC, Herodotus referred to Keltoi living around the head of the Danube and also in the far west of Europe. The etymology of the term Keltoi is unclear. Possible roots include Indo – European kel ‘to hide’ or to impel. Others have claimed it to be Celtic in origin; another meaning has been suggested as “the tall ones”. Most native Scottish Highlanders have always been known as the Gael, and their native country they have always termed Gaeldoch, the land of the Gael. It has been claimed that the G has usually the sound of C, which brings it nearer the primitive Celt, from which it is unquestionably derived; and whether it signifies the fair men, the hardy or strong men, the men of the woods, there is a strong link between the Celt and the Gael. There is a passage from a very old book (the History of Brition – The Scottish Gael) where it is written; ‘there appears no room to doubt that the Celtic Gael was the root of the Latin for Caledonii implying that the Celt and Gael are the of the same source of origin’. Is the ancient Celt a Gael? Also, in the same book it goes on to say; ‘they acknowledge themselves Albanich, inhabitants of Albion, an appellation which to this day is given them by the Irish’.

The word Celt according to some etymologists may derive from; Selt – ‘prehistoric instrument with a chisel edge’. Celt was a word used by Greek and Roman writers from the 6th century BC to describe the barbarian people of much of central and Western Europe. To the Greeks and Romans any other culture group of people were barbarians in their eyes.

It is well documented that the early Greek shipmasters navigated around the mysterious isles on many occasions, as early as 300BC and most likely further back in time. They often referred to the isles as Alba or Albion (meaning “white”). Alba pronounced “ullapa” is derived from an obsolete adjective “alb “meaning white, and alp was originally a snow-capped hill or mountain as in the name of the Alps mountain range of Europe. The Greek explorer Ptolemy spells it as Alouion around 127AD, and later still Pliny refers to the Island as Albion. What is not clear are they referring to all the British Isles or just the North (Scotland) as Alba?

The Vikings or Norsemen when they came over in the early 9th century and established a foot hold in the north of Scotland, called the country Pictland. The name Pentland Firth is derived from the Norse name Pettaland Fjord, literally “Pictland Fjord”. The Pentland hills in south of Edinburgh have a similar origin and refer to the southern boundaries of the Picts.

As I have mentioned Alba is the ancient name of Scotland and this is well documented throughout history, by the Greeks, Iberians and the Irish literary scholars, and Alba could be an even older name than I first thought, perhaps as far back as c. 1700 B.C. Also, the people of Alba were often referred to as the Picts or Cruithni and the Irish Annals often call the people of Alba the Albannach. The distinction here is between the land mass as Alba and the people as a different entity such as the Picts, Cruithni or Albannach; the Romans identified a number of tribes in Alba with the most prominent being the Caledonii and later the Scotii. The Roman, Eumenius, in AD 297, makes first mention to the Picts (Picti) when they are defined as enemies of Rome in the same context as the Scots (Scotii). IT has been claimed that Pict comes from the Latin Picti or pictus meaning pictorial or painted; it has been suggested by many historians that the Romans were referring to the Pictish symbols on their standing stones, elaborate jewellery, or the fact that the ancient Picts actually tattooed their bodies with designs similar to the symbols on the standing stones. There is also the fact that the Romans may have knowing about the references from the early Greek seafarers such as Pytheas who referred to the “Pretanic Islands” which literally means Picts’ Island.

The point or distinction here is that what is now Scotland, with its white caped mountains, was most likely named Alba by the Celtic settlers between c. 2000 B.C and c. 600 B.C. The early Celts never had any desire to achieve a cohesive political nationhood and they were certainly not an imperial people; therefore, the name Alba was not a national political identity by the Celts more just a name to give the Mountains and Glens of what is now Scotland.

We now know that from about 6000 years ago Iberian settlers moved up the Atlantic approaches followed by coastal farming communities who began to develop networks of communication with each other as far north as the Shetland Isles. Then about 2800BC the Beaker phenomenon saw the rapid expansion of connectivity through Western Europe and along the Atlantic sea routes, but also inland via the river systems in Scotland. The northeast of Scotland, mainly Aberdeenshire is an area rich in beakers stone cist burials and the archaeologists have recorded well over 187 beaker burials. It was during the Beaker period that the mature Celtic language developed and reached a peak during the Late Bronze Age c1300-800 BC. It is believed that this Celtic language was of the Goidelic family that was spoken from Iberia all the way up the Atlantic to Scotland and Ireland. Around 900 BC the trading links between Iberia and the British Isles are disrupted and a dislocation between the Iberian Celts and British Celts began. There is archaeological evidence that helps explain the next dislocation in about 600BC between the British Celts of the north and west from the south, I will address this further on in the next couple of paragraphs, before that a little more about the Celts.

The Celts were a group of peoples loosely tied by similar language, religion, and cultural expression. They were not centrally governed, and quite as happily to fight each other as any non – Celt. They were warriors, living for the glories of battle and plunder. There Clan – Family unity as well as their motivation may have been the perfect political model that enjoyed many sophisticated legal structures. A brilliant people with oral tradition but often very superstitious, who actively sought deeper beliefs, a practical people, but producing penetrating intellectual concepts. Celtic women were technically equal to men owned property, could choose their own husbands, and were often war leaders. Both sexes were free to have different lovers or partners, even if they were married, often they would offer their partner to an important Chief or warrior as a token of friendship and would be insulated if the offer was turned down.

Sources that are available depict a pre – Christian Iron Age Celtic social structure based formally on class and kingship or Great Chieftains and in the main the evidence is of tribes being led by a form of class system. Most descriptions of Celtic societies portray them as being divided into three groups: a warrior aristocracy; an intellectual class including professions such as druid, poet – bard – storyteller, and jurist-elders; the third group headed by the metal workers/blacksmiths; were the common workers such as farmers and others of lower rank; very often the metal worker would come under the warrior class and sometimes the intellectual class because of their revered skills. Most of the classes could be called to arms for the Chief and Clan.

The Celts were the people who brought iron working with them to the British Isles during the late Bronze Age. The use of iron changed everything; it changed trade and fostered local independence. Trade was essential in the Bronze Age, not everywhere was naturally endowed with the necessary ores to make bronze. Iron, on the other hand, was relatively cheap, a stronger ore, and available almost everywhere. Although iron had an impact on the trade links copper and tin was still important for the production of many other items that were better made from Bonze. Apart from items such as cooking pots, axe heads, rings, or bells that held a high monetary value, they used low-value coinages of potin, a bronze alloy with a high tin content were minted in most Celtic areas. Higher-value coinage, suitable for most trade, was minted in gold, silver, and high-quality bronze. The Celtic monetary system was complex and is not understood fully, there probably was a great deal of barter in their trade. There is no doubt that iron brought about a change in trading links and probably a major reason was that iron had improved the weapons of many tribal groups and brought about more warfare causing a breakdown of trade in some areas, thus causing a more independent determined isolation with some tribes that broke the friendly connections with others and even outright hostilities towards each other.

Another factor that would have played a part in hostilities was slavery, as practised by the Celts, was very likely similar to the practice in ancient Greece and Rome. Slaves were acquired from war, raids, and penal and debt servitude. Slavery was hereditary, though manumission was possible. The Latin word captus “captive” suggesting that the slave trade was an early means of contact between Latin and Celtic societies, thus brought about more sea bond raids for slaves to feed the Roman Empire and bring in more wealth for the pirate’s weather they were Celtic or not.

The patterns of settlement in Alba, the ancient name for Scotland, varied from decentralised to urban, the non-urban societies settled mainly in hill forts and duns. The urban settlements were mostly costal or on great rivers such as the Don (Celtic name Devana or Devona) in Aberdeen where there was more than one settlement between the Don and Dee rivers. The Dee (Celtic name Deva) and the Don were regarded as Celtic “goddesses” with divine qualities and sustainable water for maintaining life which demanded some form of worship and adoration by the settlements on the rivers. The name Aberdeen meaning “Don-mouth” may have started its early existence as Devona? There is a large number of Aber – names in Scotland to this day drawing our attention to the fact that there were Celtic people who made a living from rivers and therefore regarded the vicinity of water courses as preferred habitats or settlement sites. There are a number of rivers in Scotland that are believed to be from a much older language such as the: Tay, Spey, Nairn, Earn and Esk, no one knows for sure, but it is most likely some names of rivers, mountains, and place names would have retained some element of their early origins in the name.

Between c.900 and 500BC there had been changes in prehistoric Scotland where’s before there had been remarkably little changes for many hundreds of years. The changes were in the settlement types with hillforts; a hilltop settlement defended by one or more ramparts, the appearance of stone built Brochs in the far north, and Duns – strong holds built on top of natural rock structures.

Hillforts were timber laced and began to appear from c. 900 and 700 BC, when the Bronze industry in Scotland was particularly flourishing. Such timber – laced forts are fairly widespread, but the greatest concentration is in the heart of what became Pictish strongholds in central and eastern Scotland along with the Moray Firth. Many of the forts are the vitrified remains of what was once a fort where the timbers in the ramparts were fired and the stone of the ramparts were fused into a slaggy mass from the burning of the core of the ramparts to a high degree. As to why this was done, deliberately or accidently, has not been established but finds from excavated examples suggest that they were being constructed until the fourth century BC.

As well as these forts there were simpler farmsteads within enclosures with low ramparts and ditch that were made to keep marauding animals from straying in as opposed to a form of defence. Many settlements were of the round huts type built from wood and thatch, common on open settlements are souterrains that were most likely food stores. These souterrains are underground passages usually lined with stone and connected with above ground huts.

Some crannogs were still in use, basically a house or small settlement on an artificial island, found mainly in Lochs, all though many are from an early age as far back as the Stone Age – many were taken over and used by the Celts.

Most of the Duns were built on top of a rocky outcrop, or a sea cliff rocky outcrop, were constructed mainly from wood but often stone would be used as well. The names of many of the Duns are still in use to this day such as Edinburgh (Din Eidyn), Dunnottar near Stonehaven Aberdeenshire, Dumbarton on the River Clyde, and Dunadd in Argyle, to name just a few.

A separate cultural tradition might have developed from the early Iron Age of Northern Scotland with the Broch towers of stone that were built in large numbers. The northern and western isles and the main land north and west of the Caledonian Canal, this was the province of the Brochs (often known as ‘Picts’ houses’ in Scotland). More debate has surrounded the study of Brochs in Scotland than almost any other aspect of Scottish archaeology. They were still in use up till the first century AD and possibly longer. There are about five hundred Brochs in Scotland some elaborate examples have survived such as the Broch of Mousa in Shetland. Mousa is the best preserved that stands 13M today, and originally must have been at least 15M high, it is 15.2M in diameter, and is built from drystone with a single entrance flanked by guarded chambers in the thickness of the wall. They all had hollowed walling with internal staircases and internal timber ranges. Many different theories have been advanced about Broch origins; they were certainly the centres of ‘villages’, which clustered round them, perhaps numbering thirty to forty families, whom could take refuge in the large towers when an enemy approached. It has been suggested that the Brochs spread from Orkney to other parts of the Atlantic province, indicating a major powerhouse having started and flourishing out from Orkney and controlling a large area of the north and west. During the Romans attempted conquest of the northern lands of the Caledonians, led by Agricola, the Roman fleet was sent north to try and subdue the threat from the Orcadian’s, between AD 83-84, giving further evidence that Orkney was a possible kingdom.

Scholarly handling of the Celtic language has been contentious owing to scarceness of primary source data. There is also a lot of disagreement between scholars as regards the P-Celtic and Q-Celtic classification according to the Insular verses Continental Hypothesis. Although there are many differences between the individual Celtic languages, they do show many family resemblances and share core root origins with similar words to each other.

There is now more evidence to support the Goidelic language family as the spoken tong of the whole of the Celtic British Isles, the Goidelic language came from its origin of western Iberia and spread up the Atlantic sea coastal areas eventually spreading inland over time, and this would include all of the British Isles, especially Scotland and Ireland.

Furthermore, the ancients named various tribes of northern Britain years before the Romans set foot in Britian and one of the most famous of all were the “Brigantes”. Some scholars believe that the Brigantes were named after a Spanish Celtic King. Breoghan (or Brigus or Bregon) who was king of Galicia, Murcia, Castile, and Portugal, and may have even reigned further south in Andalucia – all of which he conquered during the expansion of Celtic culture into Spain. The name “Abregon” is still quite common in northern Spain. King Brigus after conquering lands and establishing new kingdoms sent a colony of his people into Britain. His invaders settled in the northern counties of modern-day Durham, Lancaster and Cumbria. These settlers were named after him and were called “Brigantes” by the Greeks.

Of these ancient kingdoms, Galicia is still one of the seven recognized Celtic nations. The word means “The Land of the Gaelic People”. It is from Galicia that the Irish legends claim that the Irish race sprung from. There is also a possible link to the Picts, King Brigus had a son named Bile, and was also a Celtic King of Spain. Several Pictish Kings were also called Bile, including its most famous King, the destroyer of the Angles at Dunnichen in 685 AD.

The name Bile is of high interest to students of Celtic mythology. To the Celtics of mainland Britian he was called Bel or Belinus, to the Irish he was Bile. In some texts, he is said to come to Ireland from Spain. The fires of Beltaine were lit to mark his recognized feast. He was a powerful ancestral deity to the Celtic races.

Bile’s son was Milesius, perhaps the most famous of all the Celtic Kings of Spain and father of the Irish race. As a youth Milesius, distinguished himself as a warrior in Egypt and was also known as Galamh, in Egypt he was called “Milethea Spine,” (meaning the Spanish Hero). Legend says, because of his powers as a warrior, Milesius was given the hand of Scota, daughter of the Egyptian Pharaoh. From her name comes the name of the Scottish people. He took her back to Iberia and they reigned as King and Queen. There are a number of other legends that all have similar links to Scota as a daughter of an Egyptian pharaoh and either being married to various other heroes’ or eloping with them to Iberia. One plausible tail claimed she married Geytholos (Goidel Glas), the founder of the Scots and Gaels after her exile from Egypt, some sources claim he was a king of Greece, others have him as a Scyrhian. Another source has him as Niul, son of Fenius Farsaid; Niul was a Babylonian and scholar of languages and was invited by the Pharaoh of Egypt to take Scota’s hand in marriage. Scota and Nuil had a son, Goidel Glas, the eponymous ancestor of the Gaels, who created the Gaelic language by combining the best features of the 72 languages then in existence. There is also a connection to the Stone of Destiny that involves Scota and how she had the stone transported with her to Iberia; perhaps it was a wedding gift from Scota fathers the Pharaoh.

Other sources mention Gathol, King of Scots, who sat on the stone as his throne in the Scots Kingdom of Brigantia (Corunna) in Iberia. Another legend has Milo, King of the Iberian Scots, giving the stone to his son Simon Brec who carried it with him to a far-off land in 700 BC. The argument that Scotland, not Ireland, was where the original Scota homeland lay and was where the Stone of Destiny was taken, perhaps the Scots were responsible for the Broch phenomenon with the introduction of a king that had brought a mythical stone as his throne? There are various claims as to where the Scots sailed to before settling finally in Western seaboard of Scotland and calling their kingdom Dalriada. Most of the stories have the Scots arriving in Scotland many hundreds of years before Christ, between 800 and 300 BC, there is more evidence that the Scots may have settled in the West coast of Scotland long before they set-up a colony in Ireland.

Some people will say this is all speculation based on legends, but every legend has an element of truth, and with more advanced research in archaeology, linguistics, and genetics the more is being revealed to us. There will be more about the Scots further on, but for now it is back to the late Iron Age and some more speculation.

Another reason for the Broch phenomenon could be the opposite of what I have written above and in fact the Brochs were built as defences to keep the Scots out. The Broch building began serval hundred years before the Scots were alleged to have travelled up the Atlantic sea board and on to Scotland, however, there was an increase in the Broch building across the north during the time of their arrival and in one way or another the Scots may have had some influence with the Brochs.

There is archaeological evidence that France, the British Isles, and Ireland were part of a complex exchange network of similar artefacts with each other, and Iron may have been a driving force with this network. Then about 600BC both Scotland and Ireland seem to fall out of the exchange network and enter into a period of isolation and could explain the divergence of the Goidelic/ Gaelic language in both Scotland and Ireland.

Why Scotland and Ireland had fallen into isolation from the rest of the British Isles is not very clear? There must have been a power struggle between the Gales of the north and west, and the Brythonic Celts of the south?

There may have been different tribes of Celtic settlers that probably came from a number of different localities in mainland Europe during this period and were beginning to take over the ruling class. Each tribe or clan would be most loyal to their own family group and pay homage to the tribal chief and his or her family, therefore the Brythonic Celts were seen as a threat to Gaelic Celts.

As to why this happened is not fully understood; there might have been a power struggle both political and military between the various Celtic people from Europe and the indigenous Celts of Scotland. The Celtic Gauls of mainland Europe were a Brittonic (P-Celtic) language whereas the indigenous British Celts were mostly the Goidelic language. Perhaps over time the southern British Celts were changing their language more towards the Brittonic tong and the P-Celtic language was becoming the ruling classes preferred language. The Celts in the north were not having any of it and began to break trade links. According to Julius Caesar, the southern Britons had been overrun or culturally assimilated by other Celtic tribes from mainly Gaul (modern day France) as he identified their language as very similar to each other. This is more evidence from a classical writer that there had been a great cultural change to the British Celts of the South and that they were a more Brittonic Celt.

Another factor that came to have a profound influence was iron, it changed everything to do with trade, trade had been essential during the Bronze Age; copper and tin ore was not widely available, so trade was essential. However, iron was relatively cheap and available almost everywhere and a much stronger metal, this may have fostered local independence and more power struggles between tribes or clans, cumulating towards larger alliances or complete assimilation by the larger tribes over the smaller ones.

We can see from the Iberian Celtic legends that the Goidelic language was well established in the Iberian Peninsula with both the Irish and Scots having cultural and political roots in Galicia, in northern Portugal and Spain. One of the most significant recent developments is the growth of Celtic consciousness in Galicia, despite it not being a Celtic-speaking region for over a thousand years. The name Galicia means “The Land of the Gaelic People”, adding further evidence to the claim that the Goidelic Celtic language was widely spoken over the Atlantic maritime zone from Iberia to Ireland and Scotland. There also has been a revival of an early form of bag pipes in northern Spain and Galicia. The pipes have one or two drones only and not the three of the Scottish bag pipes.

Sometime around 900 BC there was a dislocation between the British Celts and the Hispans-Celts bringing about a gradual change with the Celtic language in Iberia where other influences were coming into play with the language there. Sometime before 900 BC we are told that the Iberian Irish Celts conquered Iern (Ireland) in c. 1698 BC. Then during the rain of Heremon, one of the first Milesian Kings of Ireland, the “Cruitnii” another Iberian Celtic people arrived in Ireland and were refused lands by Heremon; they were told to go to the land in the east called Alba, over the sea where they would find land a plenty. According to the Irish Legend the “Cruitnii” – “the people of the designs”- were in fact the Picts. I think there is some political propaganda at play here and that the Irish Legend has been tampered with to bolster a latter historical claim by the Irish Scots of Dal Riata, Antrim. I see no reason to doubt that the Cruitnii were in fact the Scots of Galicia from Iberia and were only trying to forge a trade link with their Celtic brothers from Iberia, that indeed the Scots had crossed the sea from Alba, to trade and forge alliances; and probably had been for a number of years.

It is most likely that a number of family groups from the Scots had branched out to explore and then settle other parts of Scotland and as I have mentioned above might have had some influence with Broch phenomenon in one way or another, as well as the surge in Hillforts and Duns between c. 900-500 BC.

Another reason for the migration of the Scots and could have coincided with the dislocation of c.900 between Iberia and the Atlantic seaboard of Scotland and Ireland. Was the Phoenicians had set up trade posts in Iberia around this time, and over a period of many years the link with the Atlantic Celts and their Celtic brothers of Iberia were crumbling mainly due to the Iberian trade with the Phoenicians. Also, the Phoenicians had sailed beyond the Straits of Gibraltar before the Greeks and Romans. Gades (Cadiz) in Spain was founded by the Phoenicians centuries before Carthage. It is believed that they sailed on to the British Isles and traded in a number of goods, but their main desire was Tin and both Spain and Cornwall were the main Tin mines in those days. Tin was highly prized among the Syrian nations and imported by ships of Tyre. So perhaps the Scots were not so keen on the changes brought about by the Phoenicians to their northern kingdom of Galicia and many of them began to move up to the Atlantic West coast of Scotland where they are more at home with their own Celtic brothers and sisters and language, namely the Goidelic.

The influence of iron began to take over and trade links with mainland Europe, namely Gaul, were established with the eastern seacoast as the main link from Britian to Europe. This probably brought many artisan in the metal working trade from Europe who brought their skills with them, in the working of the new metal ore, and also other influences both in culture and language (the continental Celtic language was diverging into the P Celtic around this time) would have brought about change by gradual infiltrations over many years to the local Celts from their continental cousins who were able to obtain higher rank and eventual political superiority. The Hallstatt Bronze Age culture was developing in the north of the Alps around c. 1200 BC then by c. 705 BC the Hallstatt Celts adopt ironworking then by c.550 BC their culture and trade had spreads into Britian. By c. 450 BC the La Tène culture develops in Germany and France and around c. 400 BC La Tène culture spreads to Britian eastern Austria and Hungary. From the late Bronze Age to the early Iron Age the continental Celts were spreading out across mainland Europe where they were mixing with other cultures and languages that were most likely to have influenced the changes in their own Celtic language and culture as well as trade. Those trade links were beginning to spread further into the British Isles and Ireland until 600BC when both Ireland and Scotland seem to fall out of the exchange network and enter into a period of isolation from culture, language and political influences of the rest of Britian. As a result, this could explain the divergence of the Goidelic into the Gaelic language in both Ireland and Scotland, and there is every reason to believe that the Gaelic language was widespread all over Scotland at this stage, and probably well into early AD during the Roman invasion.

Julius Caesar invaded Britian in 55 and 54 BC as part of his Gallic wars with the Celtic Gauls in mainland Europe. According to Caesar, the Britons had been overrun or culturally assimilated by the Celtic Gauls during the Iron Age and were now aiding Caesar’s enemies in mainland Europe. He received tribute, installing the friendly king Mandubracius over the Trinovantes, and returned to Gaul to continue his conquest of Europe.

From what Caesar said about the Southern British Celts having been assimilated by European Celts is interesting, we know of the trade link between Britian, Gaul and the Hallstatt La Tène Cultures. This might imply that the ruling classes of Southern Britian were overrun by the Celtic Gauls, and perhaps other European Celts. This could have been the reason for the break in the trade links with Scotland and Ireland from the rest of Britian and Europe, both the indigenous Irish and Northern British Celts were not for assimilations.

The Roman conquest of the land that is now southern England was a gradual process, beginning effectively in AD 43under Emperor Claudius, who’s general Aulus Plautius served as first governor of Roman Britian (Latin; Britannia or, later, Britanniae). By AD 47, the Romans had defeated a number of Celtic tribes and were in control of most of the land in the south of what is now England. After Boudica’s (Boadicea) uprising against the occupying Romans forces in AD 60 or 61, and after they had defeated Boudica, the Romans expanded steadily northwards taking control of parts of Wales.

There was further turmoil in AD 69, the year of the four Emperors, as civil war raged in Roam. Venutius of the Brigantes seized his chance and was left in control of the north of England. After Vespasian secured the Empire, his first two appointments as governor, Quintus Petillius Cerialis and Sextus Julius Frontinus, took on the task of subduing the Brigantes.

By AD 78 the Romans had conquered more of Britian and a new Governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola was now in charge, he was a Gallo-Roman general who had gained a lot of experience in many campaigns across the Roman Empire. After he completed the task of conquering the Brigantes, he began the conquest of the northern Celts, of what is now Scotland. By AD79, Agricola’s army reached the river Tay, however, it would take a further four years to fully incorporate the tribes of southern Scotland into the Roman province and build up to four or five major Roman forts.

In AD 82 Agricola then returned to the northern advance staidly moving up the east coast establishing a number of marching camps, aided by the Roman fleet around the east coastal water ways. It is believed that sometime in September of AD 84, from the very large marching camp of Durno, the Roman army approached Bennachie (The most favourable site of the battle) where the Caledonians were awaiting their arrival. It must have been an impressive site for both sides to look upon each other’s armies in that early September morning. So much so that Tacitus has taken the trouble to identify the site of the battle by name but unfortunately not that actual location. Grampian derives from an early printed version ‘Grampius’ which appears in the (edition princeps) produced by Francisco dal Pozzo in Milan around 1480. The original Latinised name was nearer to Craupius and this may have possibly been derived from an original Celtic word Craup or Croit meaning a hump. We are told that the Caledonii were led by a great warrior leader called Calgacus, his name can be interpreted as Celtic “calg-ac-os” and is related to the Gaelic “calgach” possessing a blade, or swordsman.

Agricola commanded between 16,000 and 20,000 battle-hardened, Roman trained, professional soldiers made up of auxiliary infantry, Roman Legions, and cavalry. The majority of the 30,000 credited by Tacitus to the Caledonians were foot-soldiers with a front line of chariots at its head. If indeed the Caledonians had raised a force of 30,000, which seems excessively high figure for the tribal levies of north-east Scotland in the Iron Age, it may have been made up from many other tribes or clans from far and wide around Scotland and perhaps northern England? The Romans gained a victory over the Caledonians after intense close-range fighting with the slain Roman figure of 360 dead, remarkably small figure, compared to Tacitus figure of 10,000 Caledonians killed. This figure is almost certainly inflated by Tacitus regards the Caledonians dead and I would think a figure of less than half of the 10,000 would be more accurate. Of course, the Roman historian Tacitus was glorying his father-in-law Agricola some fifteen years after the battle of Mons Graupius.

Agricola had served in Britian for seven campaigns and he was called back to Roman soon after his victory where he retired. Roman success was short-lived, and they were forced to withdraw part of their army from Britian in AD 87 due to heavy military defeats on the Danube, as a result most forts beyond the Cheviots were abandoned, and Iron Age Scotland remained unconquered by the Romans. By the end of the century the most northly Roman forts lay on the Tyne-Solway isthmus. Emperor Hadrian, who ordered the construction of his wall and work probably started in AD 122 or 123 and the troops were still modifying the frontier installations at the time of the emperor’s death in AD 138. Hadrian successor Antoninus Pius, decided on a new forward policy in Britian and by AD 142 the Antonine wall was built across the narrow waist of Scotland between the Clyde and the Forth isthmus, it was not long before the Romans were to abandon this new frontier around AD 161.

Some scholars say the Celtic Caledonians (Roman Caledonii) are derived from the tribal name Caledones or Calidones, which is etymologizes as “possessing hard feet”, alluding to stand fastness or endurance, from the Proto-Celtic roots Kal or Kaled – “hard” and qēdo – “foot”; Kaledion – “a hardy rough people”. Another source (The Scottish Gael [James Logan]) claims that there appears no room to doubt that the Celtic Gale was the root of the Latin Caledonii.

Unfortunately, there is no further mention of Calgacus after the battel of Mons Graupius, but there is plenty of reference to the Caledonians and the constant trouble they cause the Romans for over 200 years. In about AD 180, another Roman historian, Cassius Dio tells us, ‘the tribes in the island crossed the wall that separated them from the Roman forts, did a great deal of damage, and cut down a general and his troops’. The Caledonians had learnt from their early defeat and were more organised both military and politically and had probably unified many smaller tribes into one larger kingship, a High King, thus laying the foundations for a national identity and the desire towards a Celtic nationhood.

Within those early Clans there is evidence of a matrilineal system where the descent went through women from man to his sister’s son. The Pictish Kings List shows this system in use where no Pictish king ever succeeded to his father’s throne until the very end of the Pictish kingdom. However, this is not to say that some of the Tribes were not unilineal and traced their decent through either male or female line and in many cases, descent went through the male line. It is not so very extraordinary that the Picts could have been matrilineal while all around them were patrilineal tribes of the same ethnic group; the whole question of decent is merely one of emphasis. While there has been a historical tendency for matrilineal tribes to go over to patrilinearity, there is no iron law involved and some tribes may find that matrilinearity suits their own purposes. There is really no case for assuming that the Picts were non-Celtic people because they may have adopted matrilineal succession. In all likely hood many leaders would have been chosen because they were the best suited either politically, or the strongest warrior of the bunch, that were chosen by the elders of the tribe.

The Celtic ruling structure was never the divine-right, there was a High King elected by the lesser sub-kings, from a ruling house or clans, where the most suitable member of the royal family would be chosen for the task, but also in theory could be displaced by the ri, lesser kings; also often called Mormaors, if proven to be un-suitable for the task of High King (Arid ri) or (Ard ri).

In AD 297, the Roman, Eumenius, makes the first mention to the Picts (Picti) when they are defined as enemies of Rome along with the Scots (Scotii). Both the Picts and Scots would continue to invade Roman settlements over Hadrian’s wall, as joint forces, well into AD 384 and there is mention of further raids at the end of the century by the Picts and Scots. The Roman invaders were now being attacked by the descendants of the people whom they had set out to conquer. It is believed that the name Pict comes from the Latin pictus “painted, tattooed”, and there has been a lot of debate as to why the Romans began to use Picti instead of Caledonii. There is some who believe that a fort named Pexa on the Antonine Wall may have meant or stand for Pecti or even more interestingly Pectia ‘Pictland’. There is no evidence as to what the Picts called themselves, but their neighbours had for them confirm that the name underlying Latin Picti was certainly the name by which other people knew and referred to them. In Old Norse they are called Pettar or Pettir, in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle they appear as Pehtas, Pihtas, Pyhtas, and Peohtas. In old Scots they are known as Pecht, and the Welsh called them Peith-wyr, the name is also contained in the name Pentland Firth (Norse Petlandsfjordr); (Latin Petlandicum Mare); and in that of the Pentland Hills.

There could be a link further back, as early as 300BC, the Greek seafarer Pytheas refers to the British Isles as Pretanikai Nasoi (meaning “Pretanic Islands”), which is based on a native name for Britian (Ynis Prydain); which literally means ‘Picts’ Island’. Information contained during Agricola’s campaigns (AD 77-83), a name Pexa or Pectia, may suggest, if the hypothesis is sustainable, makes the earliest reference for the Picts and Pictland. Whatever the facts are as to how the Picts came into existence, it is most likely thanks to the Romans that the Picts became the nation of Alba for the next 600 years; but also, the Picts and the Caledonians were the same people.

Pictish was for a long time thought to be a pre-Celtic, non-Indo-European language, but some believe it was an Insular Celtic language allied to the P-Celtic language Brittonic. Other scholars believe that it was the Goidelic-Gaelic language that the Picts conversed in and not the Brittonic. Analysis of the seven surviving versions of the Pictish king lists is inconclusive, however, there are a number of Mc or Mac (Maqq) names in the lists that implies Gaelic names, and more recent scholarship is suggesting that the Picts may have spoken an earlier form of Q-Celtic Goidelic. In the 19th century, Robertson and a number of others, argued on the basis of place-names that the Pictish peoples were in fact Q-Celtic. Robertson’s arguments were based on 18th and 19th century written transcripts of surviving oral tradition, having been preserved by Gaelic seannachies for many centuries. There is more much more to the oral traditions of the Gaels and other ancient Scottish stories that have been overlooked by many scholars.

One exception to this, Nigel Tranter – the historical novelist, he gathered a lot of local information from all over Scotland when he wrote about the fortified houses and castles of Scotland (The Fortified House in Scotland) five volumes that were published back in the nineteen thirties. This wealth of information was gathered by him over many years, he visited every know castle, fortified house in Scotland even where there was very little remains of long lost buildings, by looking through local records and talking to local historians or story tellers he recorded it all and was able to use that wealth of knowledge when he began to write historical novels on Scotland’s history. With well over sixty novels covering a large period of Scottish history and various other historical factual books are a good red and a tremendous wealth of Scottish history.

I have taken a look at the possible roots of the Celtic Gale and the ancient land that was Alba, which was to become the Kingdom of Alba. Despite the fact that there is written evidence from the Romans that many different tribes were to be found around Iron Age Scotland such as the Caledonians, Picts and Scots to name a few, there is no evidence from the Romans what Celtic language was spoken by the tribes. New evidence from archaeology, linguistics, and genetics along with a different prospective of the ancient classical written works and other literature from around Europe have opened up new theories that I have tried to convey in this story. What is very evident to me is that the early people of Scotland from the Beaker people on wards developed into a cohesive Celtic people and language beginning from Iberia and spreading up the Atlantic seaboard into Scotland and this continued into the Bronze Age then early Iron Age. That a mature Celtic language developed into the Goidelic all over Scotland, Ireland, and the rest of Britian and mainland Europe. Around the late Bronze Age, the Hallstatt Celtic culture in mainland Europe begins to diversify into the P Celtic (Brythonic) language and spreads its influence over a period of centuries to France and then Southern Britian. There is archaeological evidence that some of the Hallstatt Celtic culture was coming to Scotland and Ireland both in trade as well as possible cultural influence where the ruling classes were becoming infiltrated by the Brythonic culture and language.

However, there is evidence that Scotland and Ireland detached themselves from those continental trade links around 600 BC with less artefacts becoming more evident within the trade exchange system leading to the eventual disappearance of any trade from the rest of Britian and Europe; therefore, the Goidelic and eventually the Gaelic language was left to flourish in both Scotland and Ireland without the Brythonic influences of the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures.

I don’t think that it is unreasonable to believe that the Caledonians – Picts, Scots, and Irish were all descendants of the same Iberian Celtic Goidelic people with some local cultural and language divergence between them; but, a very similar Gaelic mother tong that matured over many centuries from around 600 BC up till the late 1700 to the mid 1800 hundred’s. Therefore, the indigenous Scot’s and Irish speaking Gailes are the decedents of the Goidelic Celts from Iberia, who were the first Gailes.

In the next instalment I will continue from the Pictish – Roman conflicts through to the end of the Pictish domination of Alba and the birth of the land of the Scots.

Where I will set out more arguments and possible evidence to back up the hypothesis around the Caledonians – Picts and Scots all speaking the Goidelic and then the more mature Gaelic.

Until then take care and look after yourself and stay safe!

Alba gu bràth